It seems that, with almost every post on this blog, I must preface it with an apology for a lack of posting. This time, I think I have good reason to explain my absence.

2023 has been an incredible year in many aspects of my life. But today, given the heritage of this blog, I wanted to reflect on one major milestone I’ve finally achieved.

Since high school, I discovered my love for writing. And as with all things that I’ve dabbled in (coding, music…), my energy quickly turned towards a seemingly impossible, complex project. In this case, it was tackling the ‘elusive manuscript’. I’ve wanted to write a novel — and have been attempting to do so — for well over a decade.

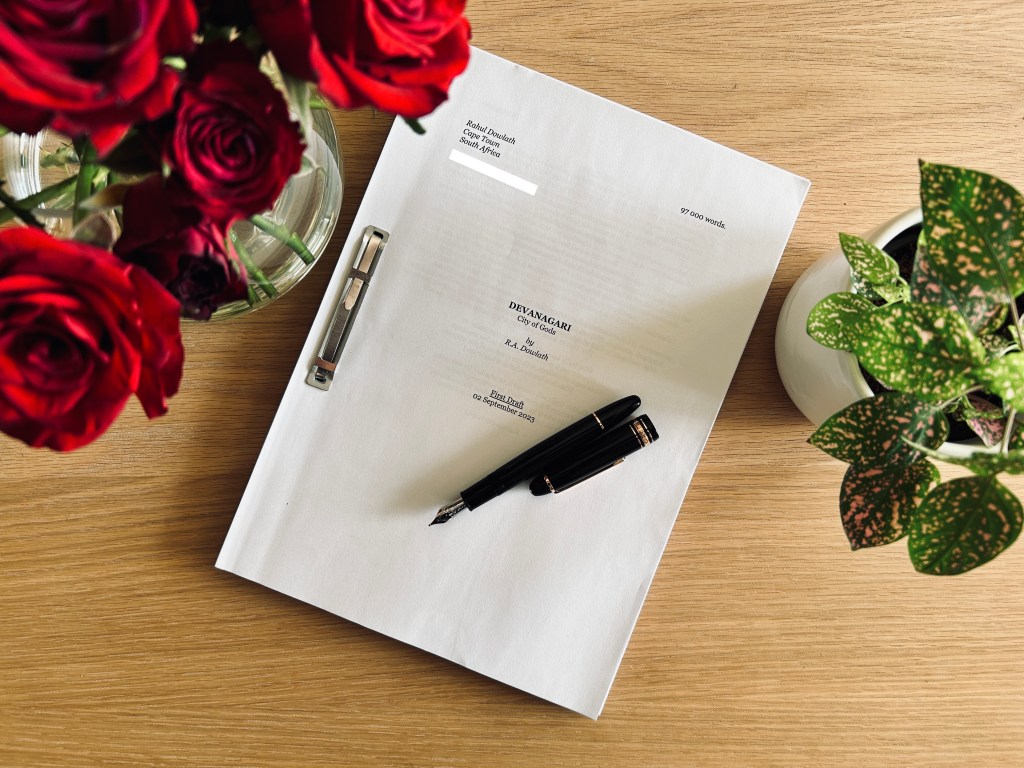

I’m relieved to say that this year, that project has finally come to (somewhat) fruition. Of course, the first draft of any long-form text is far from a completed work. There is still much work ahead for me to wrangle this beast into a discernible and coherent shape, presentable for the wider world. But that first step — putting down the words (all 97 000 of them…) has been my greatest struggle so far.

This post is a short tale of that adventure, and of nearly losing a large chunk of it. And as the year closes, it’s also a little reflection on where I’ve come on this writing journey of mine, and where I’m intending to go.

Devanagari

Devanagari: City of Gods has existed in some form in my mind and in a few failed previous starts for over a decade. Perhaps the earliest iteration came from an idea I explored during a routine English class test in, maybe, Grade 9 or so. In that moment of time-pressured composition, the idea of a dystopian city with some system called E.A.R.T.H. came to me in a flash. I was quite proud of the backronym I made up (“Energy Asynchronous Real-Time Habitat”), and wanted to use it as part of this long-format project I was slowly planning. What the backronym actually meant, and how it could fit into some sort of futuristic environmental disaster story, I didn’t quite know yet. The idea, however, suffered from what I now consider a fundamental part of novel-length development: sustainability. Many further attempts fizzled out, and then I got busy with matriculation, and university, and then work, and my writing life faded to background noise: a few blog posts here, some essays there, journaling, and long periods of silence in-between.

And then, amidst the weirdness of 2020, in that strange somnolent period between Christmas and New Year, a flash of lightening occurred. A close friend had recently gifted me a beautiful little Lord of the Rings themed notebook, with the hope that I would get back into writing. I was tinkering around with it in my Dad’s office, just jotting down ideas that had played in my mind over the past few years. And suddenly, pieces began to fall into place. Worlds began to collide. And Devanagari was born. For the first time, I had the strong feeling that this was the sustainable idea I was seeking for so long, bits and pieces of previous failed attempts finally coalescing into something that truly excited me for the first time in a long while.

To condense 97 000 words:

Devanagari is the name of the writing system of many Indic languages, particularly Hindi (which I’m trying to learn), and Sanskrit. It means ‘abode of the gods’. This alone was enticing: the merging of two facets of interest to me – ancient Vedic philosophy and myth, and not-so-fantastical advanced technology. That intersection gave rise to the central themes and ideas for the book. Ideas I knew could be sustained over the long period of time it would take to write this monster.

Without wanting to give too much away, Devanagari centres around a futuristic technopolis hailed as the last bastion of humanity. After a series of cataclysmic sociopolitical and environmental events called the Calamities, this city now houses the last surviving remnants of our species. In order to avoid making the same mistakes, and to effectively control and manage this population, a hyper-advanced artificial intelligence resides at the centre of the concentric city, quietly running the place and using the hive-mind to create a perfect image of society. It’s also worshipped by a small group as a god, a saviour of our species. Until… the machine starts to gain sentience. And a fight for our very humanity ensues.

Of course, there’s a lot more to it than that. The novel blends ancient philosophies with advanced technologies that are not that far-fetched, many of which already exist today. I’ve had fun following the imagined trajectory of our technological and social pathways, and where they could potentially converge. One of the central themes is our worship-like reverence of technology today, and the notion of what if, given this current course, we are inventing a new pantheon of digital gods?

Nearly Losing It All

The book is divide into 3 paths, inspired by a Vedic mantra: Satya (truth), Jyōti (light) and Amr̥taṁ (immortality).

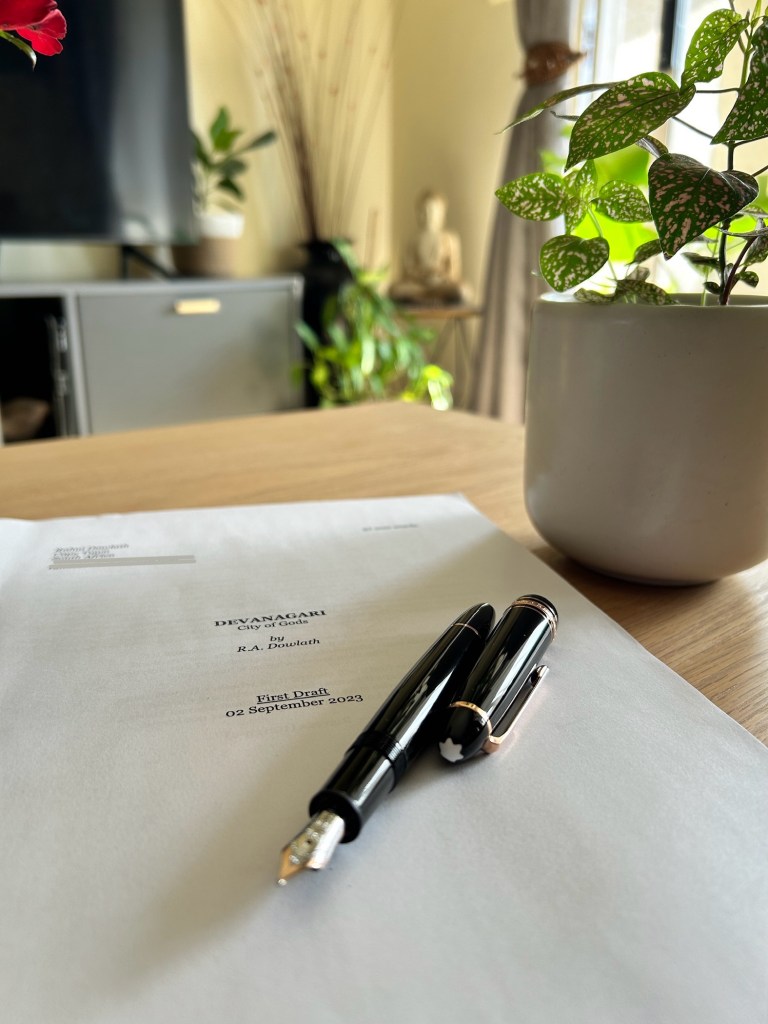

My process at first was gently teasing out the ideas on paper with fountain pen. Then, I developed the outline with Scrivener, and wrote Part 1 entirely on computer. But I found myself starting to obsess over word count, and coupled with staring at a screen all day as part of my job, and wanting to emulate writers I personally admire (Anthony Horowitz, Neil Gaiman), I thought it’d be both fun and a re-invigoration of energy into the process to switch to longhand for all of Part 2.

This would do a world of difference to the process, and also, almost, the undoing of it all.

So, for much of 2022, I wrote with my Parker Sonnet in a Leuchtturm journal. This was a liberating experience: the feel of nib on paper is always intoxicating for writers, and not watching numbers tick up to my target goal, not staring at a screen – it was a great experience.

This was also the year my (now wife) and I were planning our wedding in earnest, and as such I was travelling quite a bit between Cape Town and Durban. Somehow, amidst the chaos of planning an out-of-town Indian wedding, I managed to complete the longhand draft of Part 2. During my travels up and down the country, I moved with my journal and pen, ‘just in case…’. I also travelled light, with only a laptop bag and a black pull-along carry-on (like the hundreds of other passengers on these low-cost checked-bag-priced flights). In November 2022, for some reason, I decided to place my writing folder in the carry-on bag, rather than my laptop bag. This was the key mistake.

With South African airlines, they often ask passengers to leave their carry-ons at the door to the aircraft, usually if the overhead bins are (inevitably) full. I’ve done this countless times, and didn’t think twice to drop my bag at the door with other similar-looking ones before boarding.

So, we land in Cape Town. It’s late at night. The plane parks at a remote stand. Now, if we’d parked at the terminal, the lights at the airbridge would’ve removed any uncertainty as to the ownership of these bags. But this was not the case on that fateful night.

I’m one of the last to walk down the airstairs. Almost all the neatly-lined up bags on the tarmac next to the Boeing 737 have been taken. There’s a single black bag there. As I approach, with a feeling of anxiety engulfing me, I see that it’s definitely not mine.

In that bag were my future wife’s freshly printed invitations for the wedding, and the notes and entirety of Part 2 of Devanagari. The book was close to being dead.

It took a day and numerous calls to the airport before we could locate my bag, erroneously taken by a passenger mistaking our similar-looking bags. Needless to say, my bag is now wrapped with bright-red tape and an ugly luggage tag: there’s no mistaken identity anymore.

I’ve also ensured my writing case travels on my person, in the cabin and in sight whenever I travel with it. For this reason, Part 2 of Devanagari will forever remain particularly special for me.

The Future

This first draft, as with any novel, is intentionally not perfect. Whilst I’m an ardent planner and plotter, just getting the words onto the page was my priority with this project. That’s always been the hardest part for me. No matter how meticulous the planning is, without actually sitting down to write it, there can be no first draft. Sometimes it was hard, and there were times I stopped for a while. But I pushed myself to at least get to this point, and getting here has allowed me to feel what it’s like to fly at the altitude of the requisite novel-length word count (above 80k words).

I’ve also come to appreciate and truly understand what many writers mean when they say that the first draft is meant for the writer, that it’s meant to be messy and not perfect. I was steadfast in reminding myself of this, allowing mistakes and messiness, moving fast and breaking things in the process. The two most important things for me were that, a) I get the words onto the page, and b) that I was writing this first and foremost for myself.

The intention is to, ultimately, get this queried and published. The road to getting that final book in my hands and on my bookshelf (and, hopefully, in the bookshelves of stores all over) is a long and complicated one. It’s going to require many revisions and fixes before the manuscript is ready for the wider world.

For now, I’ve let the work rest for a few months. Distance will be key to the editing process, allowing for refreshed eyes and a clearer mind when I get to fixing this draft. In the meantime, I’ve actually begun what could potentially be a new series. This is, once again, exciting me to remain in the realm of writing. It’s refreshing to be working on this next project, which is completely different from the Sci-Fi world of Devanagari. Having taken myself to the realm of 90 000+ words, and sustaining that idea over a long period, I now have a good sense for the shape of what a novel feels like from the perspective of the creator, rather than the consumer. I feel like my writerly muscles have been stretched; there is an elasticity to the process now, a sense of the contours that allows me to more comfortably navigate more novel-length projects. And the tools I’ve acquired from slaying the dragons along the path to this first manuscript will be invaluable as I embark on the next project, this potential trilogy.

The energy and excitement of the process fuels me, and I look forward to the day I can eventually share Devanagari (and this new project) with you. And, of course, I hope (but can’t promise) to write more on here about, well, writing. There’s much to still talk about on process, the tools, the methods… but for now, I’m ready to dive into the next one.

Leave a comment